If you want to speak with the media, then you need media training.

Never confuse a reporter for a friend.

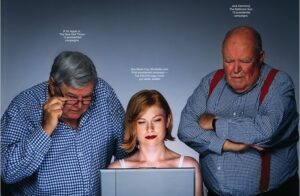

This conflation is often the first — and most damaging — mistake that people make when engaging with the press. After all, it’s tempting to get chummy with a reporter. He’s a professional listener who’s eager to quote you. In the glare of the spotlight, you get seduced by his charm and let your guard down.

But here’s the thing. Reporters have a job to do: To serve up the news in a way that’s interesting. You, too, have a job: To promote your side of the story. Inevitably, those two missions will clash.

The Ex-Doctor

Perhaps the most famous illustration of this conflict is that of Jeffrey MacDonald and his biographer, Joe McGinniss. MacDonald was an Army surgeon who was convicted in 1979 of stabbing to death his pregnant wife and two daughters. Yet during the trial, MacDonald was so convinced of his own innocence that he invited McGinniss to write about his case, then he gave the reporter full access.

MacDonald thought the reporting would exonerate him. In fact, it did the opposite. The resulting book, Fatal Vision (1983), further incriminated the doctor. Indeed, not only did it portray McDonald as a “narcissistic sociopath”; it also led to a lawsuit.

And that’s only half the story. NBC went on to create a miniseries about Fatal Vision. Then journalist Janet Malcolm wrote an entire book about the interactions between the two men. Thirty years later, Malcolm’s conclusion remains a bedrock principle in every P.R. course and at P.R. agency:

“Something seems to happen to people when they meet a journalist, and what happens is exactly the opposite of what one would expect. One would think that extreme wariness and caution would be the order of the day, but in fact childish trust and impetuosity are far more common.”

In other words: Reporters don’t make dependable friends. Don’t confuse attention for agreement.

The Ex-Marine

What’s that you say? Only an idiot would be this dumb?

Well, consider this: An eerily similar story occurred in 2015. A marine named Mark Thompson had been convicted of five offenses, including indecent conduct, yet a board of inquiry later concluded that he should have been acquitted.

Like MacDonald, Thompson figured that a media profile would gain him sympathy in the court of public opinion. So he asked a friend to approach a reporter from the Washington Post.

But in the course of reporting, the reporter came into possession of text messages that, once again, did the exact opposite. Here’s how the resulting profile concluded:

“On April 13, 2017, Thompson finally admitted in a military court that he’d been lying for years about the case. He pleaded guilty to the charges against him at Marine Corps Base Quantico. For his crimes, he was expelled from the Corps he’d served for two decades and sentenced to 90 days confinement. His wrists and ankles were shackled as two officers escorted him down a long hallway toward the car that would take him to his cell.”

Don’t “Be Yourself”

Here’s another dangerous, yet surprisingly standard, piece of advice: “Just be yourself.” That’s good guidance for a job interview, where you’ll spend every day for the next X years. It’s terrible for a media interview, where your quotes will live online forever. Let me explain.

Talking with a reporter is not your typical, everyday chat. Indeed, it’s not even a conversation. It’s a cautious communication intended to achieve a specific purpose.

Accordingly, a media interview demands a specialized form of discourse. As the trainers at the Throughline Group explain, “You have a message to share and a way you want to share it — and that will likely mean a few adjustments to your usual style.”

Let me put the point this way: For me, “being myself” means being casual and care-free. It means sporting flip flops and cracking inappropriate jokes. In this milieu, it’s easy to slip and share something I’ll later regret. (Just ask my girlfriend.)

By contrast, when I talk with a reporter, I’m on my best behavior. For one thing, I wear a business suit. That armor tells me that the given exchange is professional, not personal; this is business.

For another, I don’t wing it; I workshop my talking points in advance. That allows me to appear polished and poised rather than risking an ad-libbed gaffe.

Put simply, I’m not “myself.” I’m the best version of myself.

Focus

Some people think the point of media training is to teach you how to lie. They think spinners like me help people shade and evade.

That’s absolutely false. The point of media training is to help you convey your point without getting distracted. In a word, it’s to help you focus.

That’s a critical skill because it doesn’t come naturally to most folks, especially in our attention-deprived, endlessly editable age. Instead, as with most things in life, the only way you gain a new skill is through lots of trial and even more error.

Indeed, contrary to conventional wisdom, no one is born a communicator. That’s because communication isn’t an art. Communication is a scientific process, one that you can study and master if you focus.

So what are you waiting for? If you want to speak with the media, then you need media training. You have nothing to lose but your mistakes.

Jonathan Rick helps professionals perfect their executive presence, whether through media training, public-speaking coaching, or slide-deck development. To schedule a free consultation, visit his website, JonathanRickPresentations.com.

A version of this article appeared in PR Daily on July 15, 2020.