One for human beings and laymen; the other for search engines and insiders.

One of the greatest daily struggles faced by every professional, in every field, is to resist the allure of argot. That is, we think it’s easier and quicker to use jargon than it is to spell out and explain what a familiar word means.

This idea is hard to argue with, especially when we’re writing for people who are as knowledgeable about the given topic as we are. Yet even in those esoteric cases, it’s often better to use plain language.

This principle is particularly important when it comes to headlines, or titles. In general, your headline should speak to the public; you want to avoid insiderism. Let me explain by way of an article from last week’s Time magazine.

Francis Collins

The article was written by Francis Collins. Now, if you’re like most people, then you don’t know who Dr. Collins is. At the same item, chances are you’ve heard of the NIH, or the National Institutes of Health.

Thus, Time’s headline is not:

“Francis Collins Lays Out His Vision of the Future of Medical Science”

It’s:

“The Director of the NIH Lays Out His Vision of the Future of Medical Science”

See the difference? Most people understand what “The Director of the NIH” refers to, even though they can’t identify Collins by name.

Michelle Obama

Here’s a second example. In 2010, Jezebel ran a story about the Photoshopping of Michelle Obama for a magazine cover. The original headline was as follows:

“Good Housekeeping Gives Michelle Obama a Photoshop Facelift”

On the advice of Nick Denton, Jezebel’s owner, the website rewrote that line as follows:

“Michelle Obama Gets a Photoshop Facelift”

Denton’s explanation: “People actually know and care about Michelle Obama; only media insiders care that much which magazine it was.”

NIH Director

At the same time, you shouldn’t abandon your insidery instinct altogether. If you look closely, you’ll see that Time published two headlines for the NIH article: One for humans and one for search engines.

Here’s the headline for humans — it’s the one you see in the usual place, at the top of the article:

“The Director of the NIH Lays Out His Vision of the Future of Medical Science”

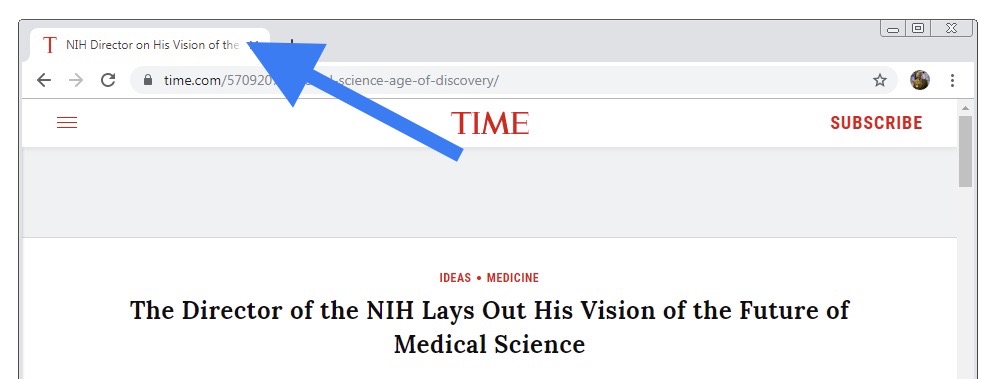

But if you look not at the webpage but in the given tab of your browser, you’ll see wording that’s slightly different:

“NIH Director on His Vision of the Future of Medical Science”

Here’s a screenshot:

Why the difference? The headline for humans focuses on what makes the most sense for readers. Readers enjoy digesting complete thoughts; they appreciate eloquent phrases.

By contrast, the headline for Google (the HTML element known as a “title tag”) focuses on what makes the most sense for search engines. And search engines revolve around keywords; people seem more likely to search for “NIH Director” than they would “Director of the NIH.”

Similarly, search engines don’t value filler words like “lays out”; they’d prefer you just said “on.”

Ray Kelly

Admittedly, Time’s two headlines aren’t terribly different. Here’s another example, this time from New York, where the contrast is clearer.

The headline for humans:

“What’s Eating the NYPD?”

The headline for Google:

“Why the NYPD Is Turning on Ray Kelly”

As you can see, the human headline is playful and abstract. By contrast, the Google headline is straightforward and keywordy. It turns out you can be an insider and an outsider.

Sweat the Small Stuff

At this point, some of you are surely wondering, Are these details really worth thinking about, let alone implementing?

Let me answer that question this way: Many of the web’s top publishers — places not only like Time.com and NYMag.com, but also NYTimes.com, NewYorker.com, BusinessInsider.com, Vox.com, and VanityFair.com — incorporate this two-headline technique into their editorial guidelines.

They do so for a simple reason: Sweating the small stuff is how we turn perspiration into perfection.

Jonathan Rick is a ghostwriter who specializes in thought leadership. He usually writes about two dozen headlines per article. He’s available to deliver workshops on the art and science of headline writing.

A version of the above article appeared in PR News on October 31, 2019.